What are state machines and why use them?

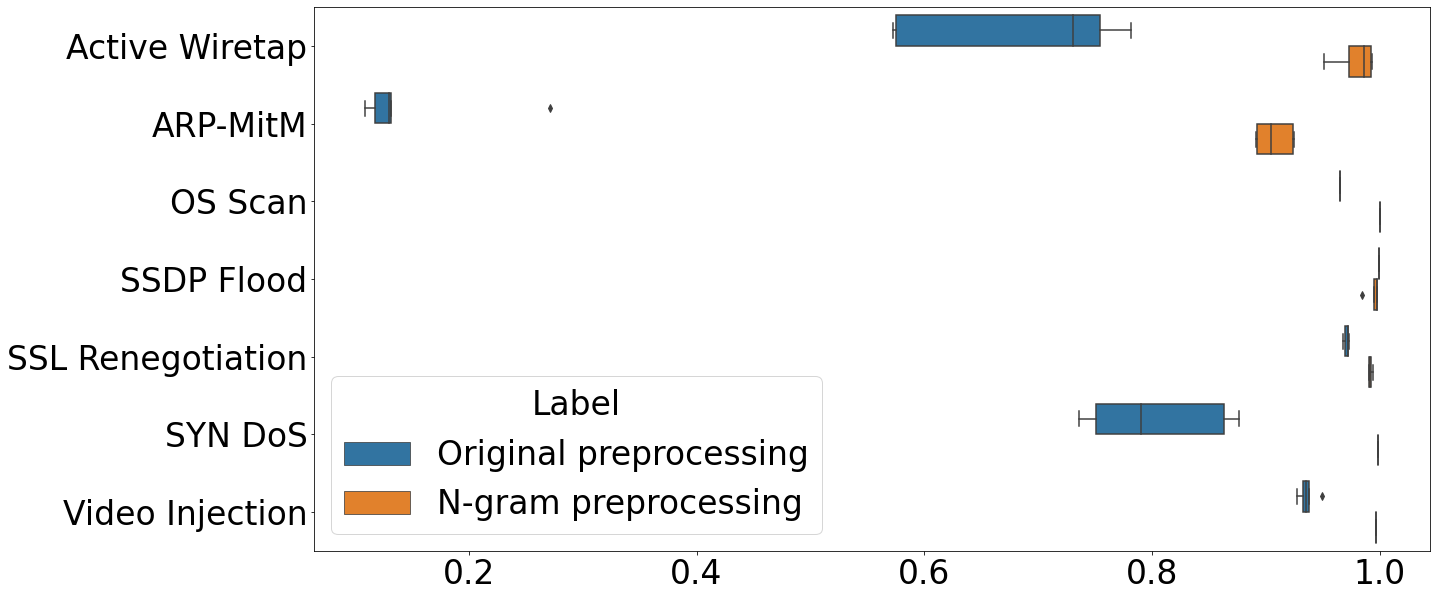

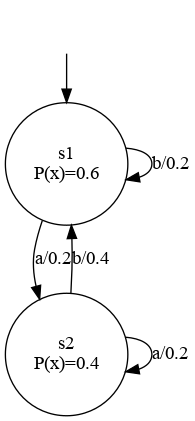

In simple terms, State Machines are discrete event systems. They consist of discrete states,

transitions in between those states, and events triggering those transitions. Below is an images

of a very simple state machine, consisting of two states two simple events 'a' and 'b' triggering

the transitions. In addition to the described above the transitions are also associated with

transition probabilities, making this particular state machine a probabilistic state machine.

What can we do with state machines? State machines have many applications and can be used whereever

a discrete event system exists. The classic illustration example is a coffee machine. For instance, we can

have take the states 'No water', 'No beans', 'Ready', and 'Coffee brewing'.

Upon starting the machine it goes into default state, checking whether water is there. If not, go into

state 'No water' and display a warning. Once water is there, do the same with the beans. And only when

water and beans are there a selection is possible, marked by state 'Ready', after which we transition

into state 'Coffee brewing'. A finished and brewed coffee then triggers another check for recourses,

either landing in state 'No water', 'No beans', or 'Ready', meaning the whole cycle repeats.

Well, that example works, but it is so simple. Why would I do the work to design a state machine in first place?

Simple state machines are mostly a domain of smaller systems. For example,

controllers in embedded system design are often first modeled as a state machine before translated into

code, adding a layer of code security on critical applications. The interested learner is referred to

this excellent course. An advantage of that method is also that other techniques such as model checking can

be employed to ensure code testing. A book recommended by a former instructor is the

Principles of Model Checking.

What if I have something that is more complex than a controller? In cases where a system is too large

to be designed by hand, or where we want to understand an existing system, we have to employ automatic

algorithms to infer those state machines for us. This is called State Machine Learning, and it comes in

two flavors: Active and passive learning. In active learning, we have access to an existing

system, and we generate inputs to ask the system for its output. A downside of this method is that we need

access to the system, and we need to be able to reset it to a default state, making learning potentially very

costly. On the contrary, if we do not have access to the system, but instead already have execution traces,

such as software logs, we can use passive learning. This method of learning simple aims to

generate a state machine model from the set of execution traces that we give to the algorithm. A downside of

this method is that it is highly dependent on the quality of the existing data, and of course on its vastness.

Learning state machines via efficient hashing of future traces

R. Baumgartner, S. Verwer

Published: LearnAUT 2022, Paris, France

Link: https://learnaut22.github.io/programme.html

There are many works on learning state machines from existing data. However, few works deal with the

modern problem of learning from data streams, which arise for example in servers that should not be

interrupted, systems that generate large amounts of data, and other kinds of systems that run

day and night. To infer state machines from these kinds of systems we have to design special kinds of

algorithms, that enable the state machine learning algorithms to continuously learn and update a

model. Additionally, these kinds of algorithms need to be able to compress information if necessary,

since the data stream can be infinite at the worst.

To tackle these challenges we designed a simple algorithm, with two main ideas: The first is the

heuristic used to identify states and transitions. In order to compress information we

summarize the stream of data in the Count-Min-Sketch data structure. These summaries are then used

to find statistical patterns, subsequently used to identify the states. The second idea is a

routine that we can use to periodically output state machines. We opted for a simple routine that

periodically saves the current model, while not interrupting the learning process.

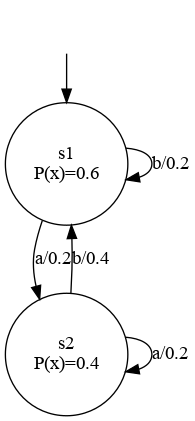

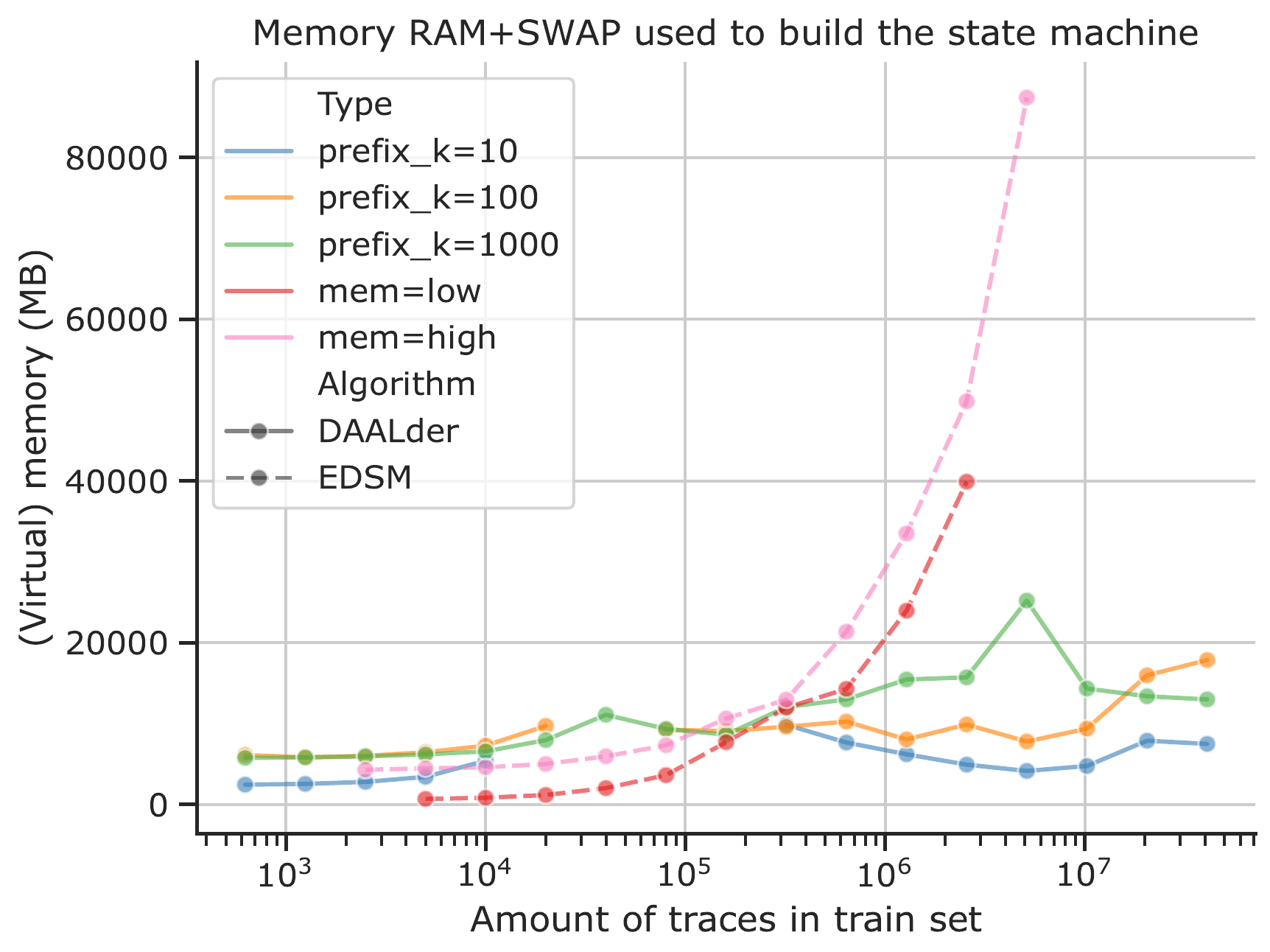

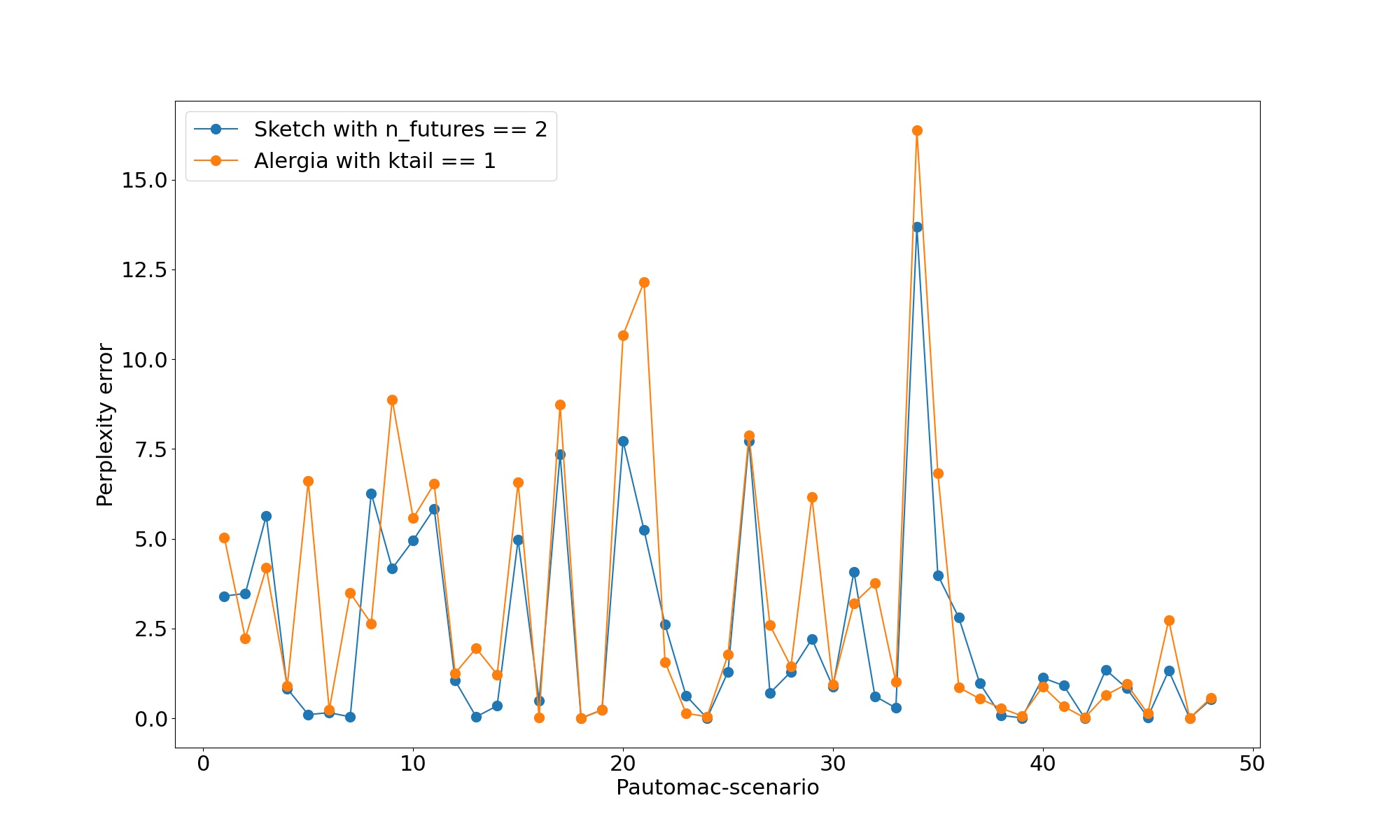

We compare our method with a well-known method to show that it is doing reasonably well, given that

it works with compressed, i.e. not full, information. Below is s figure showing partial results, for

a full description and results please refer the publication.

Learning state machines from data streams: A generic strategy and an improved heuristic

R. Baumgartner, S. Verwer

Published: International Conference for Grammatical Inference 2023, Rabat, Morocco

Link: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v217/

Continuing our work 'Learning state machines via efficient hashing of future traces', we

improve on it in the following ways:

-

Better data compression: As already mentioned, we use this Count-Min-Sketches structure to compress information.

However, we can further improve on this by using appropriate hashing-algorithms to compress

similar information together. We use

Locality-sensitive_hashing with the metric of choice being the Jaccard-distance. This approach

also saves us run-time.

-

Better learning routine: The previous routine was geared towards outputting a model periodically.

While this helps us having models without interrupting the system that is being inferred, mistakes the algorithm

makes at early stages due to having not seen enough data can lead to even more mistakes in later stages.

Balle et al. solve this problem by first

mathematically determining a sample size that is deemed safe enough before making decisions. However, this

sample size can be potentially huge, and the decisions can still be wrong. We opt for a different approach,

where we enable the search routine to reconsider its decisions.

-

Mathematical proof of convergence (PAC-bounds): Since our algorithm learns statistically from data

that is statistically generated as well, we cannot give a formal proof of correctness without making unrealistic

assumptions. However, we can employ the

PAC-framework to give statistical guarantees on the learning algorithm. We provide this work with a thorough mathematical analysis

showing formal PAC bounds. However, due to space constraints we could not include the proof in this work, but it will

be included in my PhD thesis. I will update this section with a link once it is published.

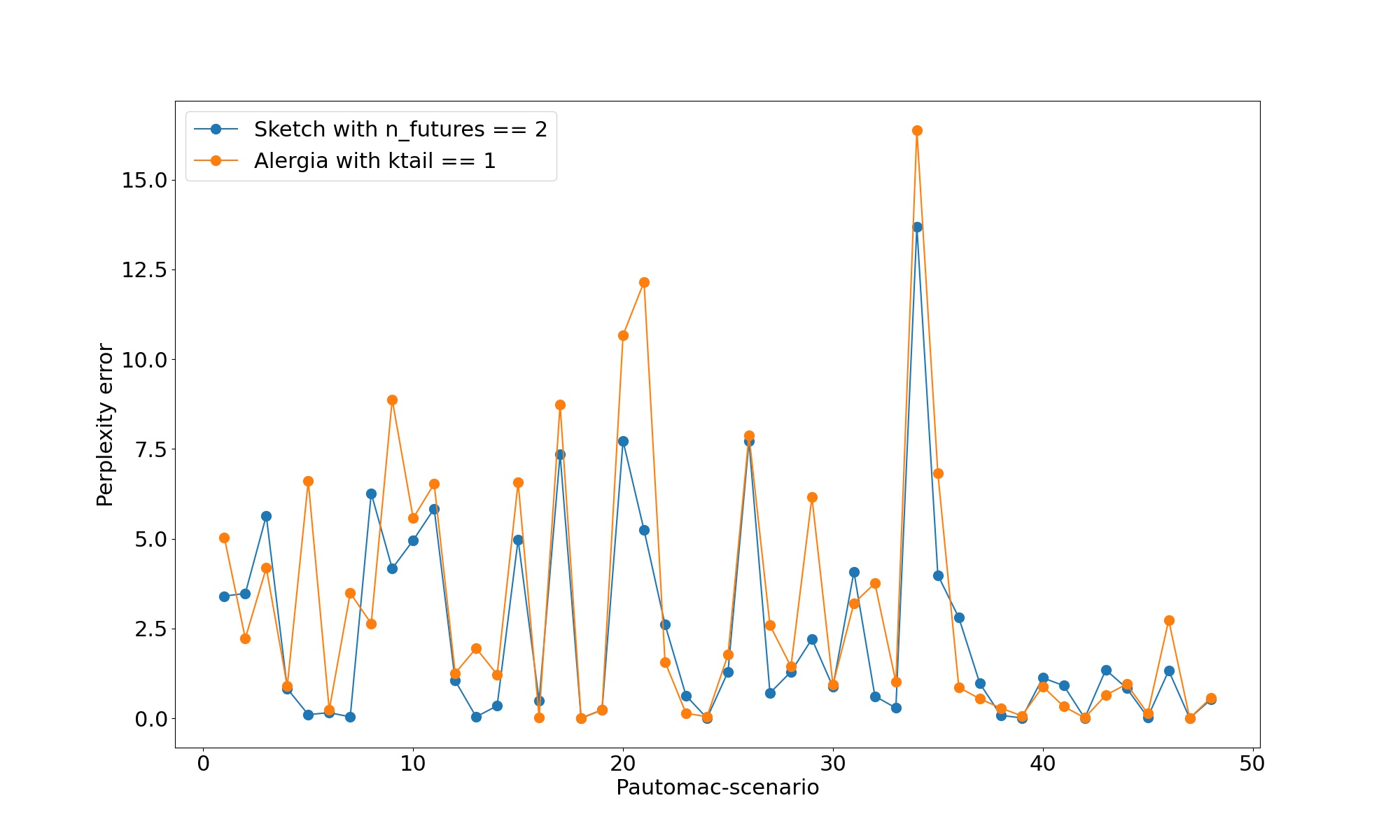

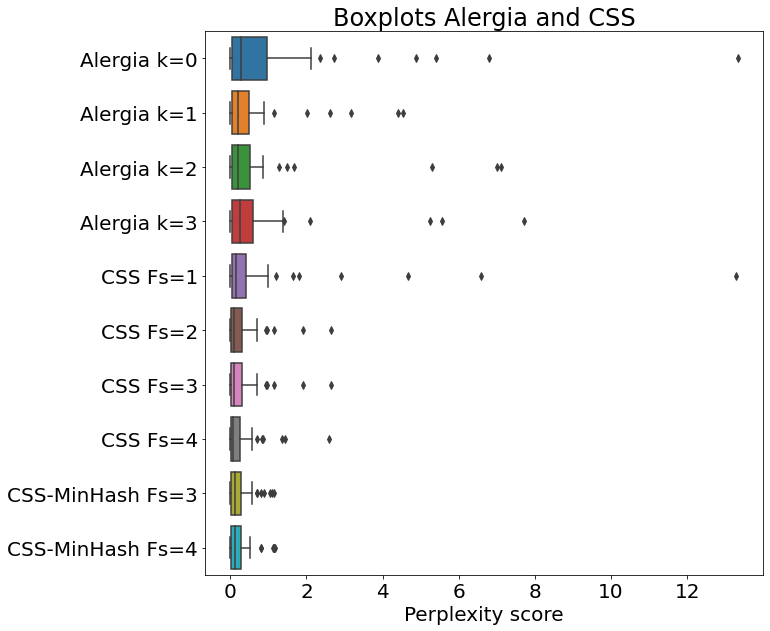

Partial results are below, summarized as box-plots. For the full picture please consult the publication.

Database-Assisted State Machine Learning

H. Walinga, R. Baumgartner, S. Verwer

Published: LearnAUT 2024, Tallinn, Estonia

Link: https://learnaut24.github.io/programme.html

In this work we take another view on the problem of limited memory. To overcome the limitations we use a database

to store the data, and subsequently employ active learning to build a state machine from the data that is being

stored in the database. We show that this approach is capable of reducing working memory and reduce the amount of

data used as input to the algorithm by employing targeted queries, when contrasted with classic passive learning

approaches.

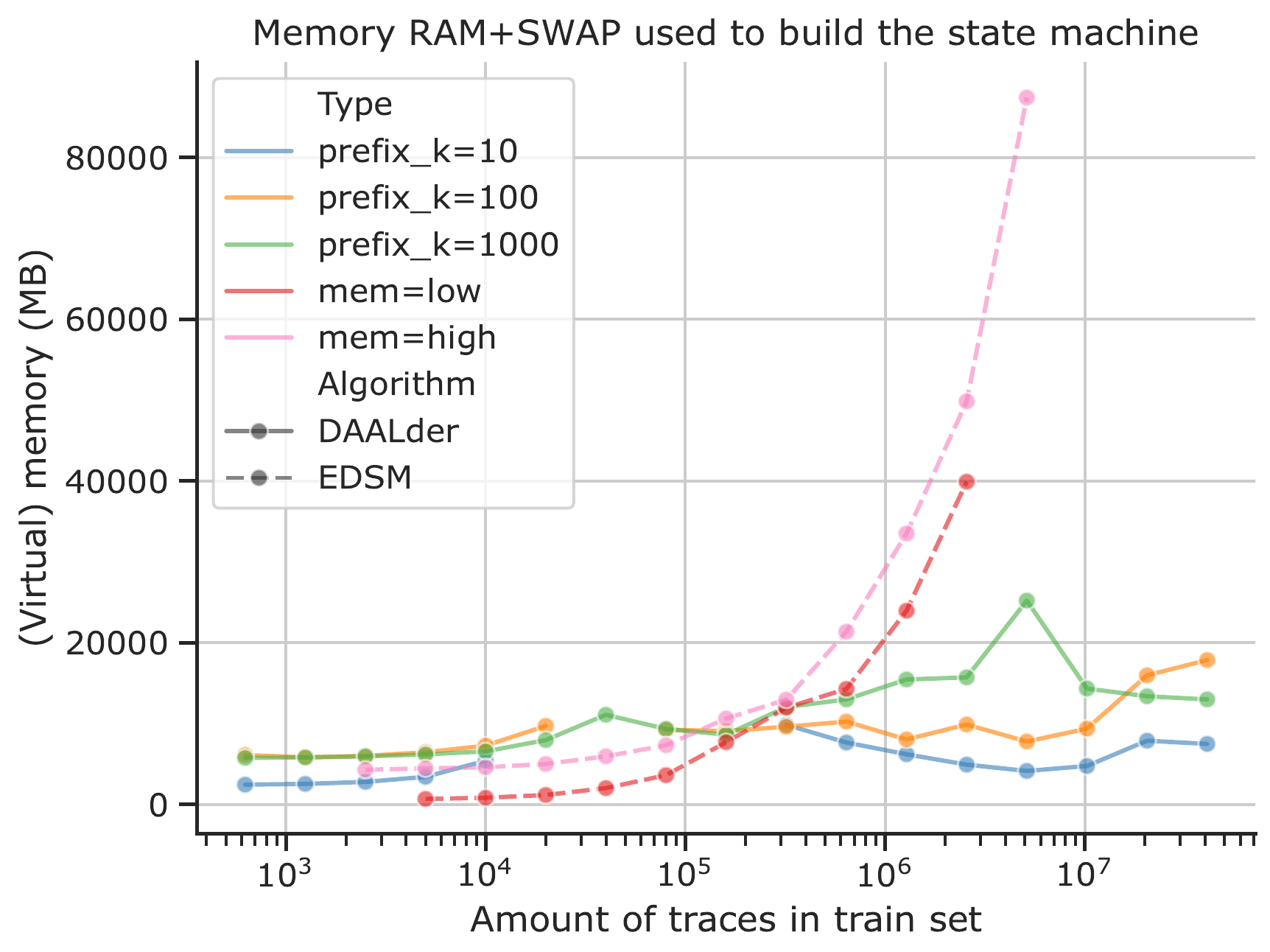

The below figure (generated by H. Walinga) compares working

memory footprint of the two methods compared. For more information and results consult the publication.

PDFA Distillation with Error Bound Guarantees

R. Baumgartner, S. Verwer

Published: International Conference on Implementation and Application of Automata 2024, Akita, Japan

Link: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-71112-1_4

Probabilistic state machines have the potential to be used as surrogate models for language models, where they

provide a reverse-engineered and visualizable model whose output mimics that of the language model. Recent

works explore the possibilities of how to extract those surrogate models from neural networks functioning as

language models. In this work we design an algorithm to extract probabilistic state machines from a given

language model and test our approach on networks trained on public datasets. We further provide proof

of correctness of our algorithm.

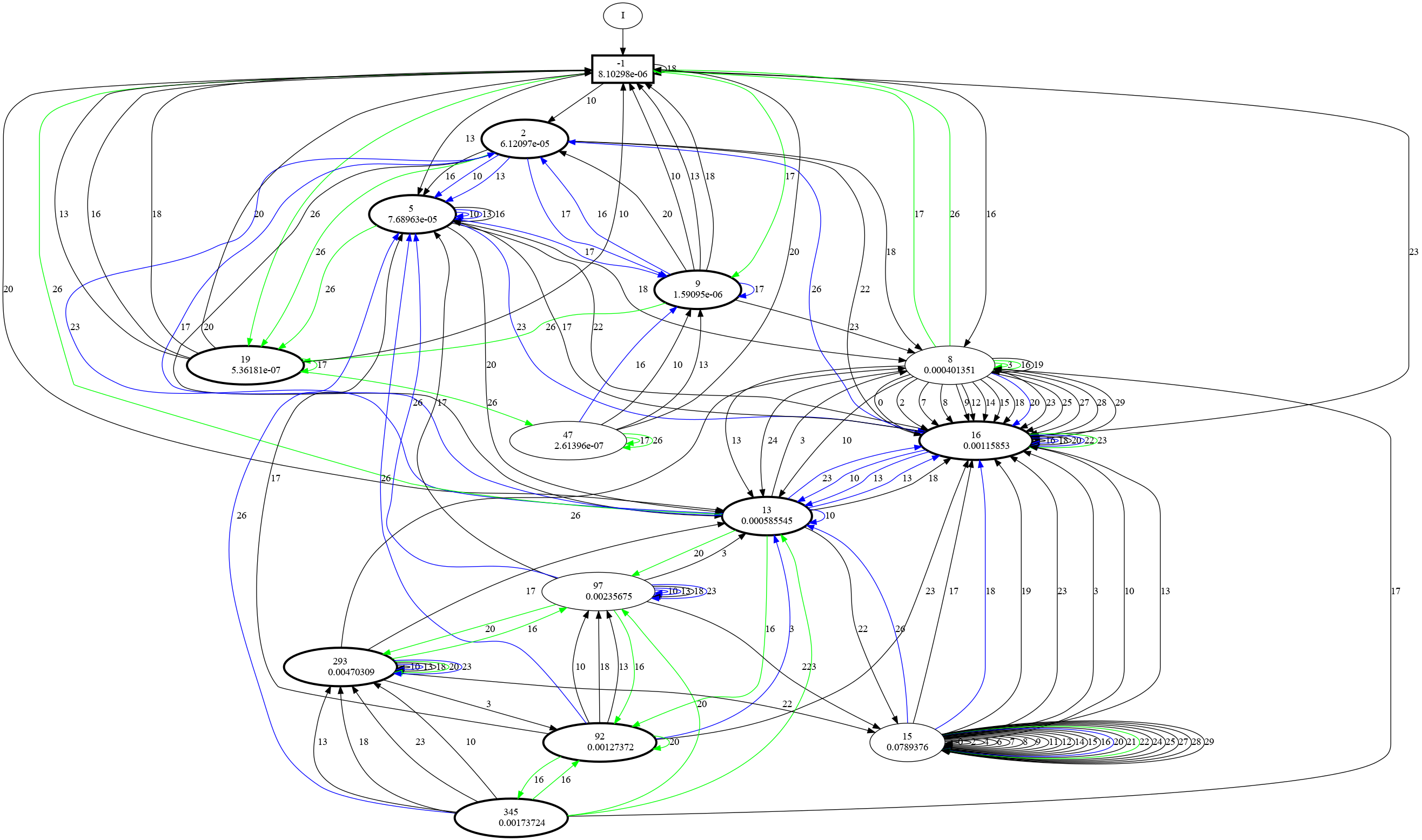

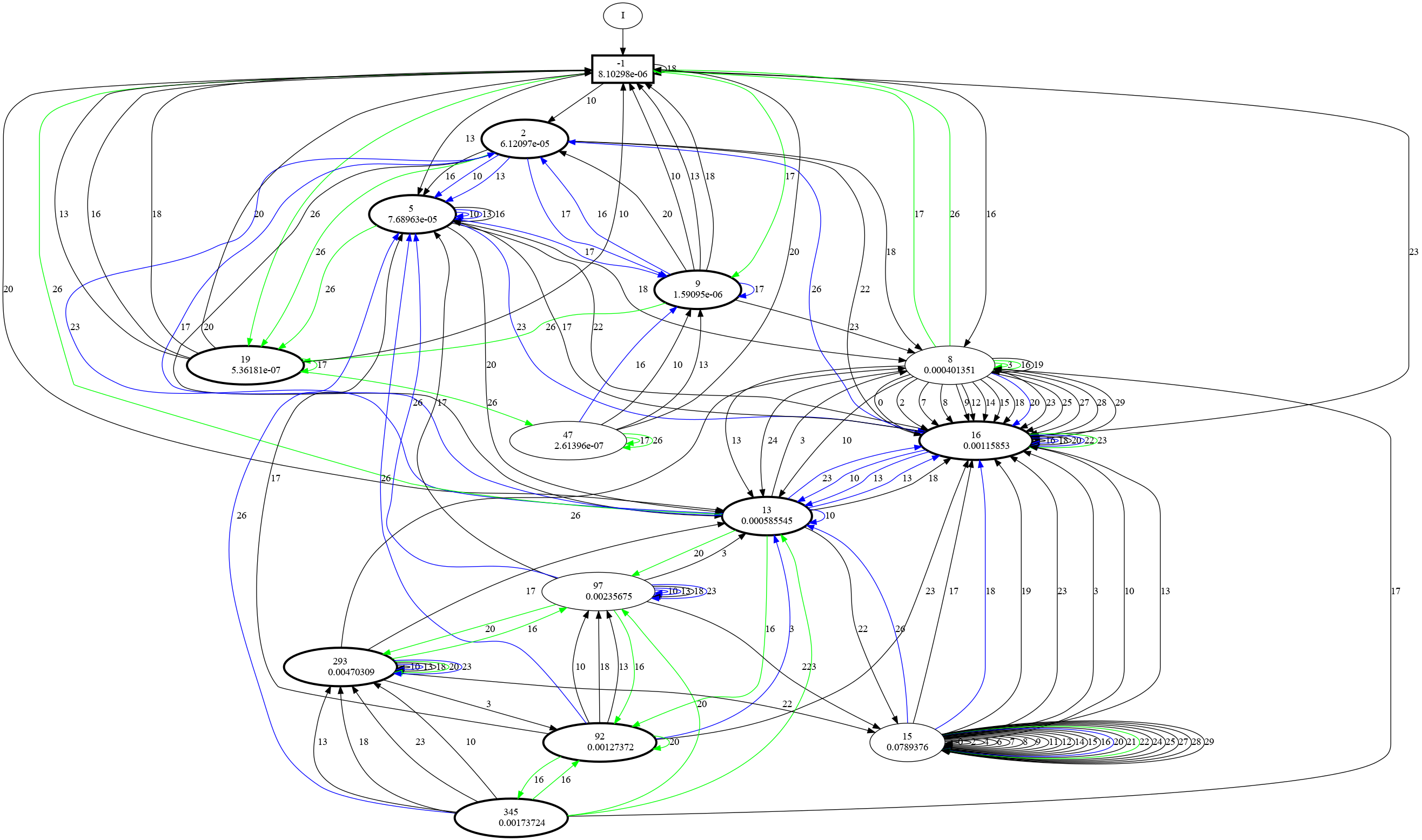

The following figure shows an example of an extracted state machine model. In our publication we exemplify how

the extracted model can be used to debug the neural network, as well as predicting faults in the data that

the language model was trained from.

PDFA Distillation via String Probability Queries

R. Baumgartner, S. Verwer

Published: LearnAUT 2024, Tallinn

Link: https://learnaut24.github.io/programme.html

This work presents a variation of our algorithm presented in 'PDFA Distillation with Error Bound Guarantees'.

This variant of the algorithm infers transition probabilities to build a model from the probability

that a series of events occur. This enables the algorithm to work under different constraints. Proof of

convergence of the inferred probabilities is provided.

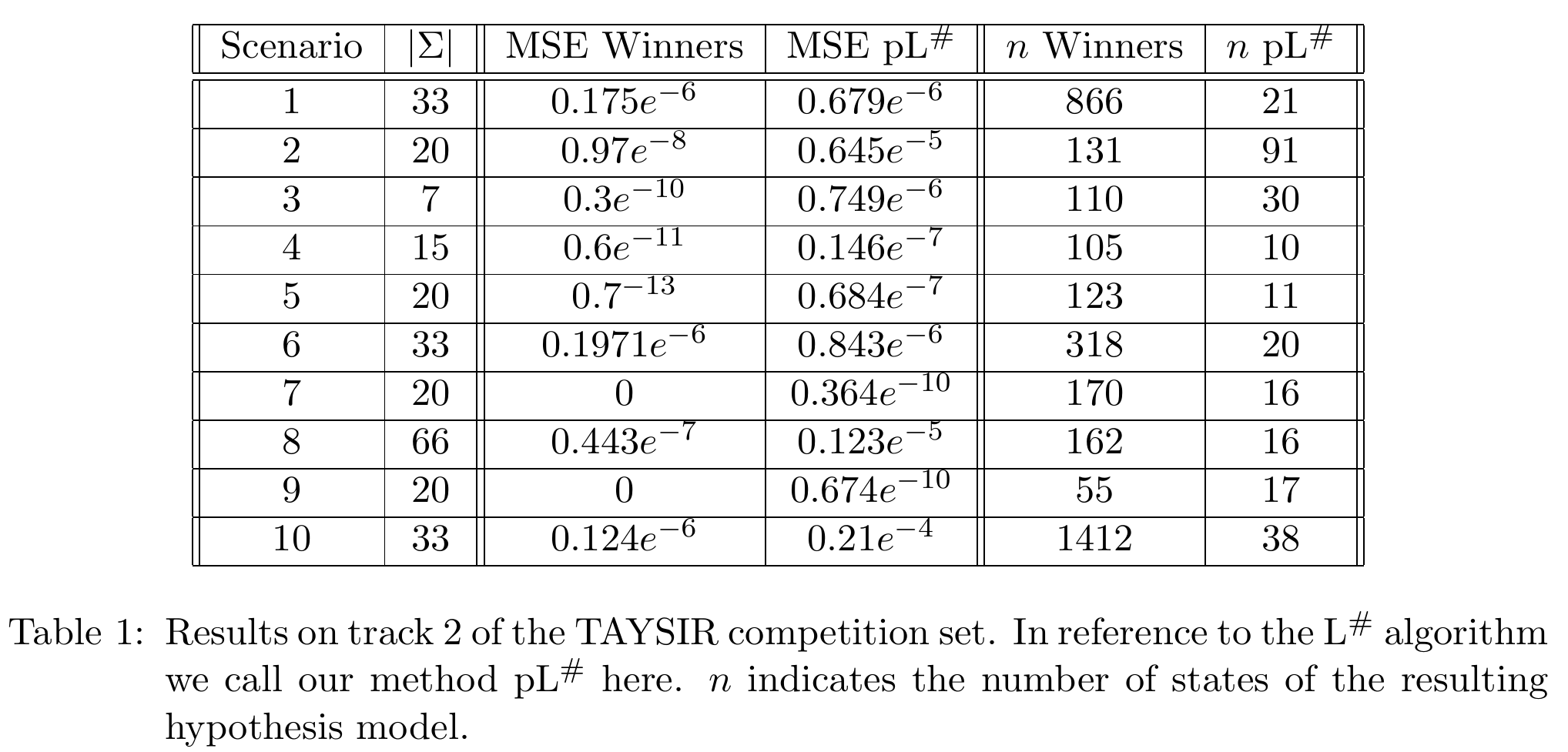

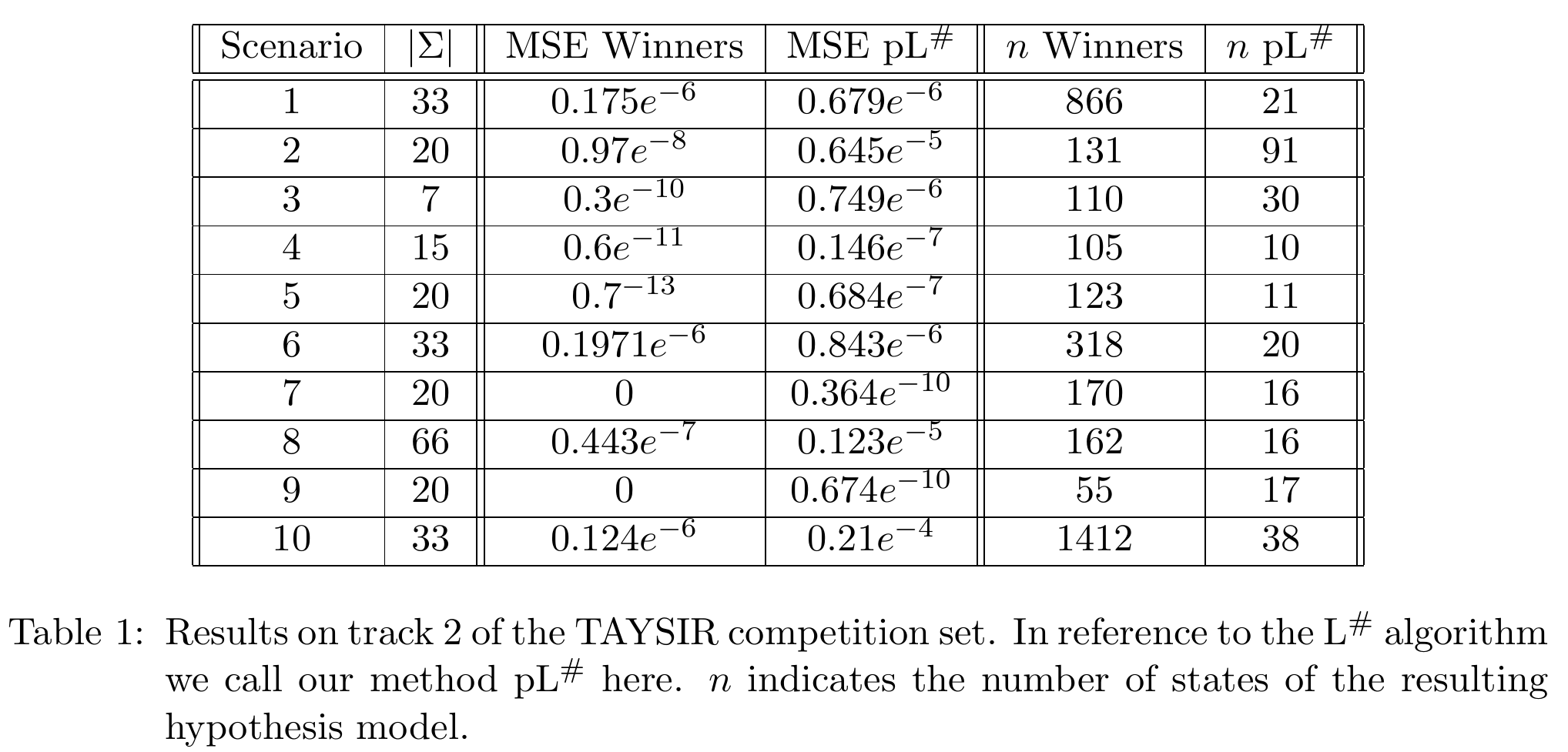

The table below shows the results on a dataset modeled for the recent

TAYSIR competition, contrasting with the actual

winner of the competition. For more information, as usual consult the publication.

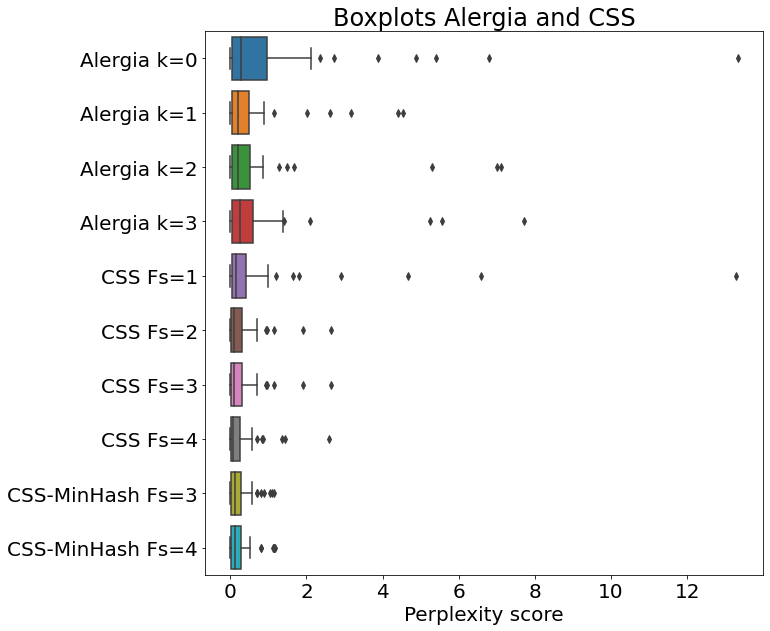

Preprocessing of cybersecurity data for anomaly detection

R. Baumgartner, S. Verwer

Published: Unpublished

Link: -

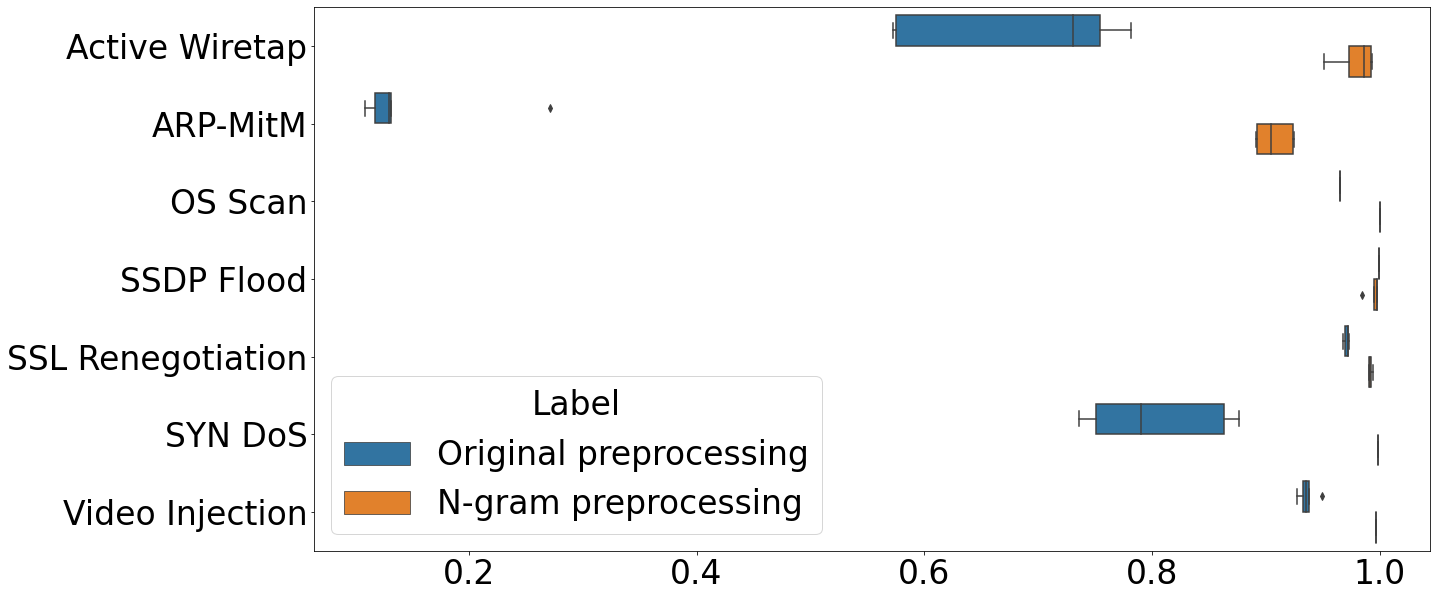

In this unpublished work we originally explored machine learning algorithms to raise better alerts when

cyberattacks happen. Our algorithms were supposed to be working on the Netflow-capture level within

a network. However, we quickly learned that the algorithm had much less of an impact on our detection

performances compared with how we preprocessed the data. This has led us to instead investigate proper

preprocessing techniques, resulting in a concrete pipeline and subsequent ablation studies, with which

we empirically show the impact of each of the preprocessing steps.

We did our study on multiple datasets and with multiple machine learning methods. In the end the

preprocessing method performed best with a simple

autoencoder model, which resulted in strong performance. The publication will be linked later,

perhaps after a simple arXiv upload.